We don’t need another Black star, Notes on Gabriel Moses’ monograph

The book acts as some sort of retrospective or memoir while offering little comment on his work’s Black visual lineage. So, can we talk about it?

Welcome to the first – albeit late – Capital Letter. I had to get some things out of my head and written down, and it took some time. It’s quite long, but let me know your thoughts, and I am happy to lend the book to anyone wanting to see it for themselves. - YAC

“At the opening of the Basquiat exhibition at the Whitney last fall, I wandered through the crowd talking to the folks about the art. I had just one question. It was about emotional responses to the work. I asked, what did people feel looking at Basquiat’s paintings? No one I talked with answered the question. They went off on tangents, said what they liked about him, recalled meetings, generally talked about the show, but something seemed to stand in the way, preventing them from spontaneously articulating feelings the work evoked.”

- bell hooks, Altars of Sacrifice, Remembering Basquiat, Art in America, 1993

Now who is this Regina? A collective parable. Love from and for the Black grandmother, mother, daughter, sister, aunty and niece. Something to be proclaimed. A collection of muses, angels, guides. Gabriel Moses has been sure the name, given to his practice and studio, travels through his cult following like the eponyms in reggae and dancehall - take Barrington Levy’s Sister Carol, Frankie Paul’s Sara or Cocoa Tea’s Sonia. The work belongs to the Black tradition and sits at the vanguard of imagery with its Afro-futurist nod to the past. But something is missing and the monograph, Gabriel Moses: Regina, shows just how the Black image is muddied in the hands of white industry folk.

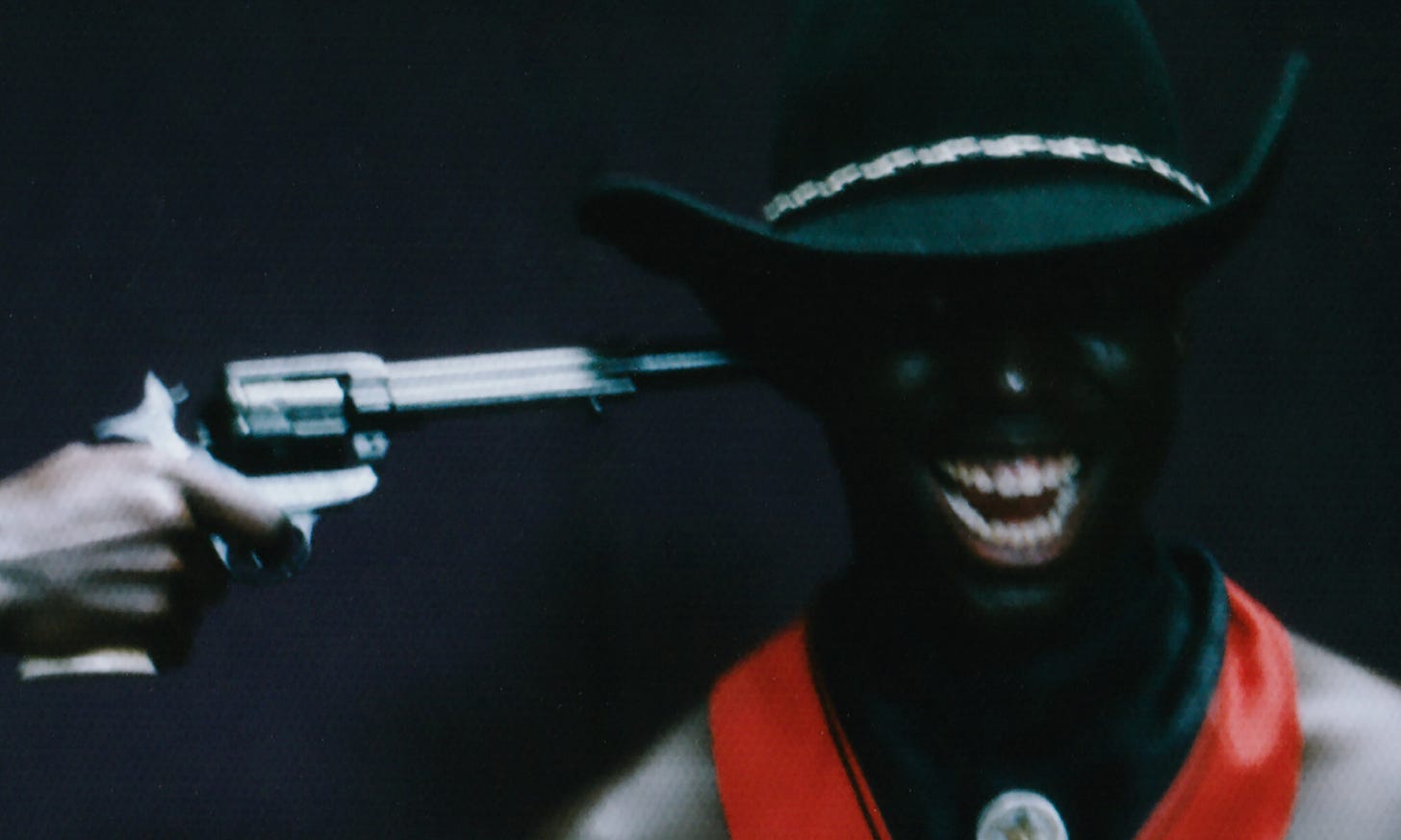

In its opening, Gabriel Moses: Regina acts as a series of vignettes-as-odes. At first, we’re presented with what feels like a split screen exhibiting the artist’s coming-of-age, from the boy who heard his mother proclaim “Who can’t hear must feel” on one side, to the 25-year-old who gets to see her proudly testify her love for him in writing, on the other. “I owe all my gray hairs to you! Shine on son!” She writes. And after cementing that bond with a photograph of her, it commences; we knew that the artist’s moving image works were just as startling when still but now we see the form it takes when magnified. It has the staged happenstance of Blaxploitation and a balance of intimacy and detachment that brings Roy DeCarava’s scenes to mind. You can see a zoomed-in still of leopard heels that hint at a Cleopatra Jones type potentially coming around the corner. But flick over, and it lands on a completely divorced scene, maybe a man this time, maybe a figure made androgynous under Moses’ stylistic shadow. At this point, Gabriel Moses: Regina does well in showing the artist’s visual assuredness, despite many of his works being heavy-hitting commissioned pieces for the likes of Dior, Burberry, Pharrell Williams and Dazed. Here, Regina starts to feel familiar.

If art moves us—touches our spirit—it is not easily forgotten. Images will reappear in our heads against our will. I often think that many of the works that are canonically labeled “great” are simply those that lingered longest in individual memory. And that they lingered because while looking at them someone was moved, touched, taken to another place, momentarily born again.

- bell hooks, Altars of Sacrifice, Remembering Basquiat, Art in America (1993)

Throughout the monograph, Moses is regarded as a saviour of the image. You know “real images”, as GQ editor Federico Sargentone puts it (in the book’s foreword), and I’m sure many others would. Not that TikTok microwaved crap that is bad for your mind and even worse, your artistic taste (the app and other social media are used as an analogy for low-quality, instant-production multiple times throughout the book). Not the images that ‘anyone’ can snap up and share even faster. Not those images that we know are merely photographs; the ones that make us wonder how many budding poet laureates are in our midst as followers find new ways to chop it up to something good. No Moses is for real. And I agree. But the book dances around the roots.

The artist’s visual prowess is posited as a result of him being empathetic, of good character, a witness (with little exploration of what he’s witnessing), or a child of this very white, very broad photographic and artistic canon –#WhiteWritersTryNotToReferenceRobertMapplethorpeWhenSpeakingOnBlackStudioImageryChallenge. But Moses has provided every clue through his equally elusive sharing of family photos and Black cultural videos that this is an act of giving voice to what these examiners would be quick to deem as lowbrow. Moses has shown us that ‘Regina’ is a translation and we should follow that imagery.

This first came to me through the gospel. When I landed on Moses’ dedicated ‘Regina’ Instagram account a few months ago, I was met by a clip of the musical legend LaShun Pace performing as a part of Bishop Pearson Carlton’s Live in Azusa series. A few months before she died in 2022, LaShun was ushered out of the periphery by a young millennial and Gen Z audience who were enthralled by a live performance of her Act Like You Know track for its consummate nod to African American expression, its fly showcase of Black nonverbal communication and frankly, the way it quenches the nostalgic thirst for a time when gospel music was gold. After a riff with Karen Clark-Sheard (of The Clark Sisters), she bands with her sisters, Leslie and Duranice Pace – come on Duranice – in a mighty reprise that became the audio for a far-reaching (ahem) TikTok challenge, growing the general appetite for explorations of gospel music on the app, where the Kim Burrell run challenge from her live performance of the track Holy Ghost also lived.

After the video of LaShun’s performance Moses posted a still from one of his films, of a model posed with her mouth wide open, in a similar vein to gospel belting – or that Ashanti meme that I’m still convinced is a series of screenshots from deepfakes. A two-second look through the Instagram and it’s clear that this is no one-off, and Moses’ oeuvre is a result of his preoccupation with emotive reaction.

The artist has spoken openly about his Christian faith and being raised in the church and we should honour the fact that a huge part of ‘Regina’ is him tracing all he’s ever seen. We should ask him more questions as to why, dig deeper into his scope, culture and scenic influences. While the book does explore his faith through conversation and another striking ‘split screen’ set up of him next to a bold Joshua 1:3, and also touches on his childhood immersed in fashion by way of his mother’s expression and sister’s grasp of high fashion trends and moguls, it feels sorely detached from the visuals because nobody asks what he’s doing with the archive. Nobody cares to really explore how he edifies the viewer, by way of fusing the ordinary and fantasy. Nobody cares to call it Black images.

The tome is regularly interpolated with impressions written by industry names and friends of Moses. You can guess who features. Corteiz founder Clint. Wog-obsessed artist Slawn. Fashionista Ari Chanoux. A-Cold-Wall/Black British Artists Grants Programme founder Samuel Ross. Places+Faces founder Ciesay. American fashion designer Matthew Williams. A chorus confirming that the relationships you see on your explore page are something real. And a 3-part harmony: Gabriel is one in a million, too pure for the industry, and humility personified. While testimony serves a purpose, it quickly begins to jade the work. The sensation is placed on the young meteoric rise, and the surrounding clique, instead of giving back to the images as it does to us - depth. With every turn of the page it starts to read like the fashion industry’s fondness with insecurity has now set itself on the one behind the lens. Or rather a setup for a Black British Basquiat of sorts, and jah know, we don’t need another Black artist flattened by the white-led media institutions and industry that seeks to create a Black star only to feed off of their commercial value.

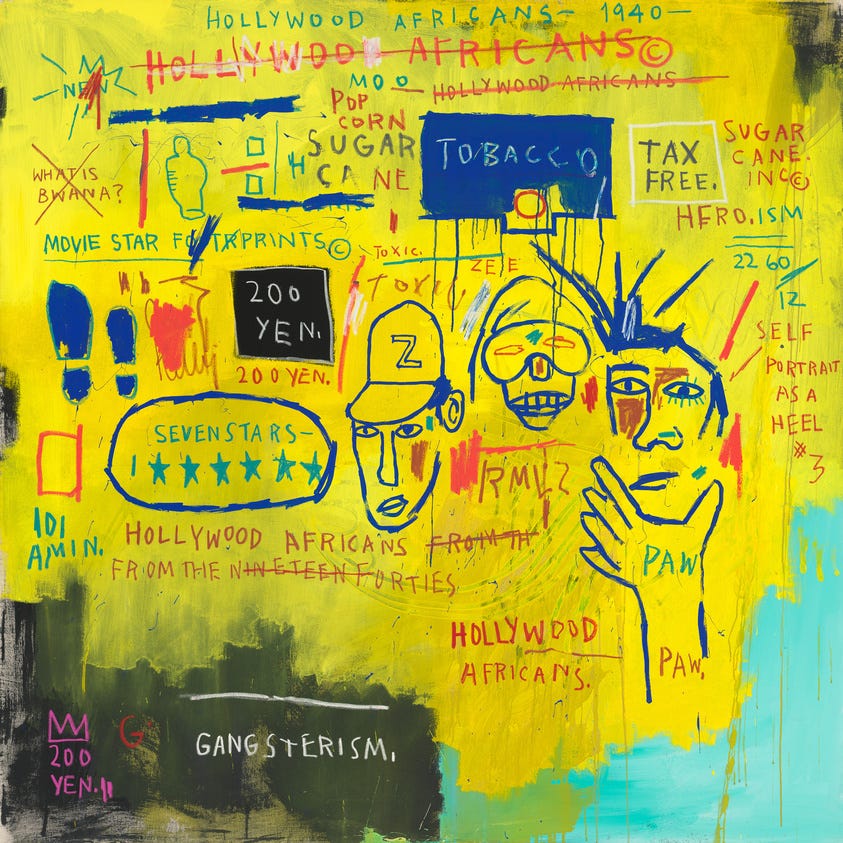

Being the same age as Moses, I spent a great deal of time on Tumblr during my teenage years and in books during my early 20s, reckoning with the fact that Basquiat was a creator of what we can call ‘Black images’. Wild I know. He’s everywhere; he’s been graced with a Primark range, the can-do-no-wrong Black billionaire couple posed with his Equals Pi (1982) painting for a Tiffany campaign, Jeffrey Wright done him to a T, and he is heralded as the most famous, most out there, most successful Black artist of all time. Through no fault of our own, many of us Black people, are still unpacking the art world’s Black Adam, because of a muddying of his work owed greatly to his commitment to that East Village silo, rife with white hipsters and attracting white critics who possessed little in the way of a suitable knowledge to unpack his themes. But, I’m often reminded of a shift I felt after seeing his piece Hollywood Africans, a self-portrait of the artist among his friends and fellow graffiti artists, Toxic and Rammellzee, who followed him from New York to Los Angeles for his blockbuster Gagosian show in 1983.

Despite the detractors who attempt to label Basquiat’s work as solely ‘American’ or ‘modern’, and his avoidance of the Black artist community/the label of a ‘Black artist’, his works are… Real Black Images. Why so much on Hollywood Africans? It’s the artwork that best captures an understanding of his position as a Black artist in that world, but also emphasises the fact that he couldn’t outsmart it. He failed to grasp just how much a lack of engagement with his themes beyond the canvas and East Village silo, would aid bastardised interpretations of his work, many of which are taken as Bible today.

Of the Black writers of the time, Greg Tate and bell hooks laid the groundwork for inquiry into our notions of formulating Black success in white art spaces, using Basquiat as both a specific case and a metaphor. Tate’s Nobody Loves a Genius Child: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lonesome Flyboy in the Buttermilk of the ’80s Art Boom published in the Village Voice in 1989, laid firm the “bicultural refugee” status bestowed on many a Black artist/intellectual and the traps of putting our faith in a Black star. Where as hooks’ Altars of Sacrifice, Remembering Basquiat published in Art in America in 1993, was a contemplative reflection on the art world’s insidious way of forcing Black artists to dim themselves, and trade their thematic depth, or talk of it, for success. Plus the fact that even after his death, nobody knew how to talk about the damn work. Over thirty years later, and the truth of this condition is going nowhere. All we can do is learn from it.

The cultivation of a Black British or African diaspora star artist is no different. Not only is the premise just as unimaginative – but not to Moses, he mentions wearing his position as one of the few Black artist’s entering these spaces “like a tailored suit!” – it’s a surefire way to ensure the work is Black enough to be gawked at by the the industry while remaining elusive enough in conversations to maintain a commercial presence within it. At the end of the day, if you talk real shit and bore them with the guts of your motif, you may lose them. But that’s what makes the book all the more bewildering, and at times, downright pathetic. We no longer have to rely on white art and fashion world pundits who can only summon a comparison to Degas’ ballerinas when looking at the Nigerian child ballerinas in Moses’ film IJÓ (I still can't believe this comparison is drawn), so I don’t see a victim here, I see an artist making a choice. Discussing Black imagery and asserting himself as the artist he wants to be, could well be done from Instagram (the platform he used as his sole sharing space until his exhibition at 180 the Strand last year), or constructed through conversation with one of the many African arts journalists on the continent and throughout the diaspora. After all, we’ve carved out a little space for ourselves since the ‘80s.

While Gabriel Moses: Regina is sharp for having us believe that an in-conversation with Skepta is important for the monograph of a Nigerian-British artist working in fashion, it contributes little to nothing to the work or its lineage. We get a bit of a backdrop; the wider scope of Black artistry is safely explored. Moses loves Nina Simone and Lauryn Hill, but offers no insight into how observing these women’s careers or even their live performances on YouTube may have influenced his portrayal of the many Black, and especially dark skin, women he shoots. But then again the interviewer, Katja Horvat, doesn’t see reason to ask. We learn that Skepta loves Bob Marley and Fela Kuti, but not enough to refrain from committing to print a whitewashed comment on their legacies and expression of their politics as “not being aggressive”.

Robert Nesta Marley, both in life and death, has been played with by skin teet commercial expressionists seeking to paint over his legacy for their comfort, ignoring the roots, and his advocacy for freedom by any means. He championed and encouraged the people of Zimbabwe to arm themselves on the road to independence in Zimbabwe (1979) and in War (1976) he recited Haile Selassie’s 1963 address to the United Nations, advocating for an end to oppression, racism and colonial forces. Until the philosophy that holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned – everywhere is war… As for Fela, in the 1970s through 90s especially, he made no blunder about his political stance on topics such as colonialism, and continually addressed Nigerian government – particularly Muhammadu Buhari’s government – corruption. Less we forget Beasts of No Nation, the track released shortly after the artist was freed from jail in 1986, after serving a sentence that Justice Gregory Okoro-Idogu, the judge on the case, admitted was disproportionately long due to pressures from the regime? A preliminary search, tells us that for both of these men, this is just a morsel of their music and efforts, they were aggressive, and certainly no weakhearts.

But that’s just the problem with the book, everything is a romantic wax, nothing is grounded. Not one journalist knows how to ask the right questions, let alone when to challenge references and answers that play it too safe. After Skepta’s comments on the two musicians, Katja Horvat enters the conversation to add that they both had “the world singing their songs word for word with many not even realising how socio-politically charged it all was”, it’s a bullshit retelling if I ever heard one, and a part of this trend of refiguring Black artist-activists of the past down to palatable heroes in order to align them with the many industry tap dancers of today. Not to mention that speaking in their respective patois and pidgin tongues renders not only the worldwide understanding but ‘word-for-word’ recitation of it all, an even lazier measure. They were regarded as aggressive by oppressive forces and figures of whom desired to maintain the status quo, and commercialised by those who wanted a piece. But most of all they resonated with the oppressed people reflected in their messaging, which is what is really important here. So, there’s pride to be taken in any and all aggression, but the book simply doesn’t care. It does here as it does throughout – dulling artistry in the quest for a perfect Black star.

Among these failings, the book also teases the realities for Moses growing up in Britain at a time of immense Afriphobia, but we get nothing in the way of an examination of the texture this takes on in the representations throughout his work. And while his conversation with the fashion photographer and one of his foremost inspirations, Nick Knight, does touch on Moses’ desire to bring his background to the foreground, “I’d say a lot of my references […] are still life, or even moments from my life and my community”, he says, it quickly descends into a careerist loo la, with endless comparison of the two men’s journeys and approach, despite the imagery baring no similarity and no shared cultural context. Nobody wants to answer to the impact of ‘Regina’ as a body of work that weaves together Black thought and traditions, instead we are to believe it’s all about her gowns.

The short of it is: Gabriel Moses: Regina wants us to have faith in a 230-page catch up with a young Black star, while leaving his themes in the wind. It’s glad to have us sit around while the fashion industry holds court and the Black image and its archival roots are silenced under its grandeur. The book sells Regina as fashion, the industry is its world, and Moses as one of its Black prophets, so all that’s left to ask now is: are we believers?

“The bottom line for people of color is that we don’t need any more Basquiats becoming human sacrifices in order to succeed. We don’t need any more heroic Black painters making hara-kiri drip canvases of their lives to prove that a Black man or woman can do more with a tar brush than be tainted by it. What we need is a Black MOMA, or, Barr-ing that, a bumrushing Black MOMA-fucker.”

- Greg Tate, Nobody Loves a Genius Child: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lonesome Flyboy in the Buttermilk of the ’80s Art Boom, Village Voice (1989)

Some references and expansions:

Sister Carol, Barrington Levy

Sara, Frankie Paul

I Lost My Sonia, Cocoa Tea

Works of Roy DeCarava, my favourite of his is Dancers (1956).

Cleopatra Jones (1973) dir. by Jack Sharrett. Valuable in the Blaxploitation canon, but white men having their hand in directing in this genre, especially when you think of the exploitative depictions of Black women and men (pimps and hoes essentially), is low down. This one is meant to be among the least stereotypical of the bunch. Take it or leave it.

Re: Robert Mapplethorpe. Black male photographers – especially Black gay male photographers – have not been able to escape the comparisons to him. A lot of the time I don’t see it. Maybe it’s a need to assemble the marginalised in one frame (ha), or just a weak understanding of photographic histories and not knowing where to refer to outside of the medium, because of course the Black arts studio photographer doesn’t have a long-lived or super consistent lineage. So just poor research and chupidness. Examples include Quil Lemons, who got the salacious headline in the New York Times, despite never saying he saw himself as comparable, and his work doesn’t ring anywhere near comparable. He debunked this for me in plain terms in a piece I wrote on his work last year though. My biggest regret is not advocating for the headline being: ‘Quil Lemons is Not to be Compared to Robbert Mapplethorpe’. Other examples are Ajamu X, Lyle Ashton Harris, Rotimi Fani-Kayode and weirdly through this monograph, Gabriel Moses.

Is Your All on the Altar, Live in Asuza 4, LaShun Pace

Act Like You Know, LaShun Pace ft Karen Clark-Sheard

Slawn enjoys painting wogs. Plain and simple. It’s not smart, groundbreaking or subversion. I’m not saying we need to employ Bettye Saar and Howardena Pindell’s 1997 letter-writing campaign for Kara Walker here, but damn when are we going to discuss the images in a not-so-nice-don’t-care-who-I-offend-in-the-clique kind of way?

Beyoncé and Jay-Z Pose with Long-Unseen Basquiat in Tiffany Campaign

Jeffrey Wright played Basquiat in the (1996) biopic. Full film here, a rarity for YouTube nowadays.

Gowns - that Aretha Franklin meme in reverse.

Absolutely stellar writing. A level of criticism and consideration that is almost entirely missing in the literary world in general, and especially in writing about photographs. Definitely makes me wanna step my shit all the way up!

very necessary commentary/critique! thank you for writing this